William L. Harkness, son of Daniel M. Harkness of Bellevue, Ohio, lived a more adventurous life than his father, who stayed in Bellevue and lived a quiet life in a small town. William enjoyed traveling, yachting, and the luxuries that his father's fortune provided him. This love of yachting seemed to run in the family, as William's half-uncle, Stephen V. Harkness, had yachts - Twilight and Peerless. Enter Gunilda, William's yacht.

Gunilda

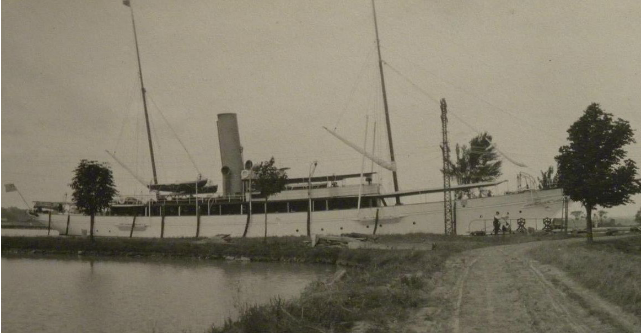

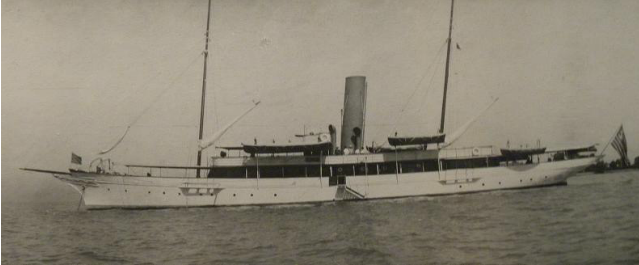

The 195ft Gunilda was built in 1897 by Ramage & Ferguson in Leith, Scotland. She was designed by Joseph Edwin Wilkins, a naval architect who worked for Cox & King of Pall Mall, London, England. She cost about $200,000 to build. That is just over $7 Million in today's 2023 dollars. Her name is a variant of Gunhild, an old Germanic feminine name meaning "war". She launched on April 1, 1897.

Gunilda Technical Details

Service History

Pre Harkness Owners

In 1902, Gunilda was purchased by William L. Harkness. Will was a member of the New York Yacht Club. When he purchased Gunilda, she was officially registered in New York City and became the new flagship of the New York Yacht Club.

In 1903, Gunilda's home port was Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, however, in 1904, it became New York City. Under the ownership of Will Harkness, Gunilda visited several parts of the world, making multiple trips around the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean.

In 1910, Harkness brought Gunilda to the Great Lakes to perform an extended cruise. Keep reading, there was a lot of monkey business that went on:

Gunilda Log 1902-1909

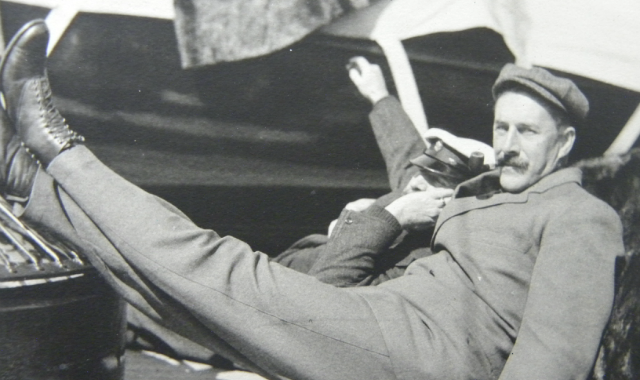

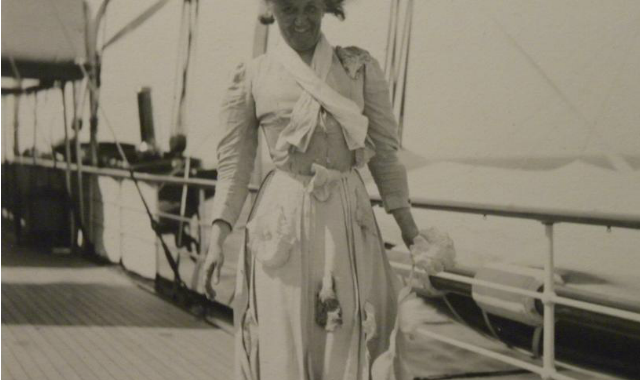

The log pictures below show the fun time the Harkness Family had with Gunilda. In the pictures, you can see the extended family including Will, Edith, and children Louise and William. Charles W. Harkness is there too and you can also see pictures of the Peerless (the black-hulled steam yacht).

A fishing trip - spoiled

In 1911, William L. Harkness, his family, and his friends were on an extended tour of the north shore of Lake Superior. In August 1911, the people on board had made plans to head into Lake Nipigon to fish for speckled trout. To sail into Lake Nipigon, Gunilda (manned by a crew of 20) needed to travel to Rossport, Ontario, then into Nipigon Bay, and finally through the Schreiber Channel.

When Gunilda docked in Coldwell Harbor, Ontario, Harkness sought a pilot to guide them to Rossport and then into Nipigon Bay. Donald Murray, an experienced local man, offered his services for $15, but Harkness declined, claiming it was too much. The following day, Gunilda stopped in Jackfish Bay, Ontario to load coal for the boilers. Harkness once again inquired about a pilot. Harry Legault offered to pilot Gunilda to Rossport for $25 plus a train fare back to Jackfish Bay. Gunilda's captain, Alexander Corckum, and his crew thought the offer was reasonable, but Harkness once again declined. As the US charts did not indicate that there were any shoals on their intended course, Harkness decided to proceed without a pilot with accurate knowledge of the region. As she was about 5 miles off Rossport, Gunilda, traveling at full speed, ran hard aground on McGarvey Shoal (known locally as Old Man's Hump). Gunilda ran 85 feet onto the shoal, raising her bow high out of the water.

After the grounding, Harkness and some of his family and friends boarded one of Gunilda's motor launches and traveled to Rossport, catching a Canadian Pacific Railway train to Port Arthur, Ontario, where Harkness made arrangements for the Canadian Towing & Wrecking Company's tug James Whalen to be dispatched to free Gunilda. The next day, on August 11 (some sources state August 29, one source states August 31), James Whalen arrived with a barge in tow. The captain of James Whalen advised Harkness to hire a second tug and barge to stabilize Gunilda properly. Harkness once again refused. As Gunilda didn't have any towing bitts, a sling was slung around her and attached to James Whalen, and she pulled Gunilda directly astern. Gunilda's engines were reversed, but she remained on the shoal. They then tried to swing the stern back and forth, but this also failed. Wrecking master J. Wolvin of James Whalen decided to pull solely to starboard, as it was impossible to maneuver her stern to the port. Gunilda slid off the shoal, but as she slid into the water, she suddenly keeled over, and her masts hit the water. Water poured through portholes, doors, companionways, hatches, and skylights. Gunilda sank in a couple of minutes. As she sank, the crew of James Whalen cut the towline, fearing that Gunilda would pull her down as well. After Gunilda sank, the people who remained on her were picked up by James Whalen.

Lloyd's of London paid out a $100,000 insurance policy..half of what it cost to build it. But the $15 was saved!

Will stayed out of the "yachting business" for a while until later when his cousin CW Harkness passed away when he took over CW's Yacht Agawa. More here on: Agawa.

Gunilda Rediscovered

The wreck of Gunilda was discovered in 1967 by Chuck Zender, who also made the first-ever dive to her. Her wreck rests on an even keel in 270 feet (82 m) of water to the lake bottom, and 242 feet (74 m) to her deck at the base of McGarvey Shoal. Her wreck is very intact, with everything that was on her when she sank still in place, including her entire superstructure, compass binnacle, and both of her masts. Numerous artifacts including a piano, several lanterns, and various pieces of furniture remain on board. Most of the paint on her hull survives, including the gilding. In 1980, Jacques Cousteau and the Cousteau Society used the research vessel Calypso and the diving saucer SP-350 Denise to dive and film the wreck. The Cousteau Society called Gunilda "the best-preserved, most prestigious shipwreck in the world" and "the most beautiful shipwreck in the world".

Two divers have died on the wreck of Gunilda. Charles "King" Hague died in 1970; his body was recovered in 1976. Reg Barrett, from Burlington, Ontario, died in 1989.

Becky and David Schott are amazing extreme photographers who dove the Gunilda and came back with incredible photos. The artistic lighting they add in these extreme conditions is extremely hard work. I am sharing their Gunilda photos here and I encourage you to visit their website at https://liquidproductions.com/

NOTE: Click on the photo itself to see all the Gunilda photos.

In 2019 a blogger on the Professional Association of Diving Instructors Tecrec blogsite named Gunilda the second-best technical diving site in the world, after the German battleship SMS Markgraf in Scapa Flow.

Video of a Dive of the Gunilda

Have you ever wondered what a yacht of this caliber looked like in their day? Here is a great video that will give you that feel:

Salvage attempts

Ed and Harold Flatt of Thunder Bay, Ontario launched the first salvage attempt on Gunilda. They used cranes and a barge to hook onto Gunilda's hull, managing to haul a piece of her mast up to the surface. They made another failed attempt in 1968, but a storm wrecked their barge and washed away most of their equipment.

In the 1970s, Fred Broennle made several attempts to raise Gunilda. In August 1970 Broennle and his dive partner, 23-year-old Charles "King" Hague, dove Gunilda's wreck. On August 8, 1970, Broennle and Hague anchored over the wreck, but there were complications during the dive; Hague dove first, dying in the process. Broennle tried to rescue him but got decompression sickness.

Around 1973 or 1974 Broennle set up Deep Diving Systems to raise Gunilda's wreck, building several diving bells and purchasing several barges, cranes, and a Biomarine CCR 1000 rebreather. Several of his earlier dives were unsuccessful.

During salvage efforts, Broennle recovered a brass grate from one of the skylights.

In April 1976 Broennle bought the wreck of Gunilda from Lloyd's of London on the condition that he could raise her. On July 13, 1976, while exploring the wreck with underwater cameras, Broennle located Hague's remains close to the wreck, near the port side of the stern, and recovered them sometime later. In September 1976 Broennle planned to dive Gunilda with his submersible Constructor, which cost Deep Diving Systems $1.5 million to design and build. Constructor bankrupted Broennle and Deep Diving Systems, ending their salvage efforts. In 1998, the story of Broennle's salvage efforts was made into a film, Drowning in Dreams.

I am pleased to see so many photographs of the Gunilda and her jouneys from her logbook(?). What was the source of those photos? I assume it must have been in the hands of the descendants of Louise Harkness, My maternal grandfather’s sister.